Read on for the transcript from this recent call with David Morgan and Tom MacNeill, CEO of Omineca Mining and Metals.

David Morgan: Hello, I am David Morgan of the Morgan Report dot com and I have Tom MacNeill with me from Omineca Mining and Metals. We're going to visit that project here but, before that, I will give a general outline of why gold right now or why silver right now. I think anyone that will be following me or Tom knows that gold is paramount in importance, especially now with the financial system that we are presently confined to. There is unprecedented money printing by governments around the world, diluting the currency that is already in existence. Watering the milk -- it never works. Unfortunately, that's the state of affairs and you could justify it or not.

David Morgan: I'm not here to get into the political debate, I'm merely here to state what I have believed for a very long time. Since I determined how the financial system works, I say that a hedge position is required by all investors. Or, basically, by all people. I advocate that I think the safest, soundest way to do it is probably with physical metal. However, I've been fascinated by the resource sector from a very early age and devoted most of my life to studying the resource sector from a top-down perspective. Why would you buy a gold mine, other than the reason that it's a good idea to have gold? With that in mind, I've looked through the sector top-down, again, from the top-tier, cash-rich major mining companies through the royalty companies, mid-tier producers, and beyond.

David Morgan: Every now and then, there's a speculation that stands out. I am very particular because it's the hardest part of the industry to get right and yet it's the most heavily advertised part of the industry. Tom, I'm gonna turn it over to you explain that. Who are you, what are you doing -- for those that don't know. Please tell us a little bit about Omineca. We'll take it from there.

Tom MacNeill: Sure. Omineca has been in existence as a company since 2012. It was created as a spin-out of another mining company. David, you are bang-on that one reason people want gold companies is that they want to own gold. The easiest way to do this to buy shares in the company that's either exploring for it or has some gold in production.

Tom MacNeill: Omineca was created in 2012 and it spent the bulk of its life idle -- I guess that's a good way of putting it -- up until this moment in time when all of those background macroeconomic factors have come into play to give us what a lot of us proceed to be the beginning of the next gold bull market. We've been holding this company back, if you will, until this time. We have a unique situation with Omineca. It's a different story if you will. It's a hundred and sixty-year-old story in some senses, even though the company was only created in 2012. The Cariboo gold rush is, without question, the richest goldfield in Canadian history. In 1859-1860, there were millions of ounces of gold liberated out of the Cariboo goldfield -- mostly as placer. In the early days, it was entirely placer gold. It's become such a unique story because of the twists of fate that I can go into in a little bit.

Tom MacNeill: Long story short, Omineca is a purpose-built company to wrap around a placer gold deposit -- a very high-grade placer gold deposit that has a tremendous amount of lode gold potential. Lode gold refers to where that gold in the placer deposit came from. The lode gold potential in the immediate vicinity of the Wingdam deposit is tremendous. Maybe there are some specific things that you want to talk about with that, Dave.

David Morgan: Thanks, Tom. It's been a while since we were together in British Columbia. I brought you as a guest of mine to the Metals Forum, where a newsletter writer asks certain companies to attend and say, "I really like this company and here's why." You did a great presentation. Dean Nawata was actually sitting next to me during the presentation. We followed up with an interview later in the day.

David Morgan: People watching this may be familiar with that or not -- maybe they heard the story for the first time. There's something about this project that I consider a bonus and that's the underground alluvial gold mining tract to the Widom project. There are impressive grades that we know about and yet you also have near-term cash flow. Would you like to discuss that part?

Tom MacNeill: Sure. Thanks, David, for taking the time today to talk about this. Now, Wingdam is a project that has been attempted for over a hundred years. It's a very rich underground alluvial gold deposit -- paleoplacer gold. It has an analogous deposit about ten to twelve kilometers upstream in the area of Stanley, British Columbia that was mined out. Uniquely, this is fifty meters beneath Lightning Creek. This presents its own problem, but that Lightning Creek is the reason why the gold deposit exists!

Tom MacNeill: Millions of years ago, Lightning Creek was fifty meters lower. It's been building through erosion of the mountainsides and it's been lifting itself up. Back in the time when it was cutting through the bedrock, it was depositing gold on bedrock under the creek. Now, that creates a mining challenge, but that's typically easy to deal with -- you just go underground and you de-water it. Let the material consolidate after de-watering and do conventional mining. In the day when they were mining at Stanley, they were just using regular timber sets for mining and having tremendous results. They mined out kilometers of that deposit, but his one didn't get mined because of something called the Cariboo slump. It's a like lake bottom silt that covers the top of the gold in some places.

Tom MacNeill: At the time of the ice age, the ice dammed up the river flows in the region and created lakes. You end up with lake sediments on the bottom and what that means in a mining sense is that it's very challenging. It retains water. And you've got the creek above it, which retains water! When you go to mine it, you cannot just de-water and start mining. This stuff starts to ooze. Eventually, you'll set up a mining room and the walls turn to toothpaste. Before you know it, your up to your ankles in water and then you're leaving the crosscut. It's been attempted on numerous occasions but the technology wasn't there to do it.

Tom MacNeill: The way we know how to do it now is with a freeze-mining project, which is tried and tested in our backyard here in Saskatchewan. It's been used in the potash industry and more recently in uranium mining. In Saskatchewan, these mining groups have perfected how to do freeze mining. It's a pretty simple process. It's no different than the process used in every hockey rink in Canada, where you simply run some brine solution through pipes and freeze the ice to make ice. Well, that's really what we do here. You go underground, you drill holes into the deposit, you run the piping, run the brine solution through, freeze the surrounding rock, and -- voila -- you've got a competent rock that you can mine simply. Usually with mechanical mining.

Tom MacNeill: What we've got is one of the highest grade gold deposits in BC history of placer mining. It's been un-mined because of the technical challenges. We overcame them in 2012 by adapting the freeze mining process to this deposit. Almost immediately after we were done and had such exciting results, the Canadian dollar price of gold dropped. In 2013, it dropped five hundred dollars in one quarter. We decided it was time to put the project on the shelf.

Tom MacNeill: My analogy for that is we took our sailboat -- our nice and shiny, fancy, new sailboat -- and instead of getting it stuck in the mud, we put it in the boat shed. We've left it there until last year. That's where we're at with it now.

David Morgan: I know from a previous interview with Dean that there's a geological similarity to Barkerville. I think he called it a mirror image of the Barkerville gold project, which has been phenomenal as far as size is concerned. There are very few these days that have not yet been discovered. Would you care to go into that?

David Morgan: I know it's speculation and forward-looking. I'll give those qualifiers, but nonetheless it's very intriguing to me that this is a district play. Could you elaborate on that, please?

Tom MacNeill: It really is. We're on the other side of the terrane. Barkerville is 25 kilometers to the east -- the Barkerville/Wells camp was originally in production back in the 1920s and 30s. It had some production in the 50s and 60s. The Cariboo gold quartz mine produced, I believe, 900,000 ounces. The Island Mountain mine produced about 600,000.

Tom MacNeill: Historically, up until the late 1950s when they stopped production, I think that complex produced about one and a half million ounces. Barkerville Gold Mines, which is now Osisko, have drilled off another resource. I believe it's something on the order of about four and a half million ounces at the five-six gram per tonne range, which means ultimately even at this early stage down there as a 6 million ounce gold camp. That's large by Canadian standards and relatively high-grade too.

Tom MacNeill: We have an analogue in that we're on the other side of the Barkerville terrane and we have all of the same structural controls. We've got the Eureka thrust fault, which comes up and over the Barkerville terrane, while they have the Pleasant Valley thrust fault that comes up and over on the eastern side. We have the same bedrock, which is largely phyllite and argillite -- relatively soft metamorphic rocks. That's what makes this so interesting and explains why there's so much placer gold in the region.

Tom MacNeill: The rock that was hosting the lode gold is pretty soft -- when you have erosional factors like ice ages, wind, and weather, that rock breaks down pretty easily. That's what enriched the streams in the area. The true analog is that Williams Creek is pretty much tied with Lightning Creek as the two richest creeks in Canadian placer mining history. They're 25 kilometers apart. They have headwaters that essentially start at the same places and run in two different directions.

Tom MacNeill: There's a genuinely interesting analogue both in bedrock geology and why the placer got degraded from the host rock and moved into the streams in the first place. One of the neat things we've got going for us is that in the seven years we've had this project, my passion has been a lot of the geotechnical work, engineering work, and other geological investigation to advance it quietly.

Tom MacNeill: While we've been doing that, Barkerville has been passed up the food chain to Osisko Gold Mines, who are some of the best explorationists in the world. They've done a tremendous job of understanding the geology in the region -- how to find gold and the nature of how it's in place at Barkerville. We get to piggyback on the wonderful information they've been creating in this intervening period. Based on all that information about the geology, we know it is a genuine analogue and we're excited to get started on the lode gold potential.

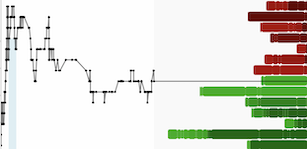

Tom MacNeill: I hope this works. I've got a couple of pictures I wanted to show for the viewers on this that explain why we're excited. One of them is part of the results from our initial bulk sample in 2012. You can see that we've got gold nuggets that were liberated from our paleoplacer that haven't traveled that far. We've got a way of determining how far the gold has traveled from the source. When you look at this, you'll see that we're over in this category here where the gold nuggets haven't been flattened. The gold grains have got quartz inclusions in them.

Tom MacNeill: Long story short, this chart tells us that a lot of this gold that we found didn't travel very far from the source. It's our understanding that some of it is probably right underneath our paleoplacer. That's what makes it so exciting. We also know that there are multiple sources of gold that charge the paleoplacer. We've recovered at least two and possibly multiple potential lode sources in the immediate vicinity or very close to our paleoplacer operation.

David Morgan: Great. Thank you, Tom. One of the things that I do as an analyst and especially on the speculative side is trying to nail down as many facts as possible, which is almost impossible on a pure exploration or greenfield type of situation. We don't do that often here.

David Morgan: What intrigued me with Omineca is the fact that you've got the alluvial gold and you've got a contract -- a fixed-rate contract. As a finance guy, I just get all bubbly because now I can do analytic work on the back of a napkin and figure out what the potential cash flow of the company is going to be. Especially when we have what's normally a variable cost for gold extraction that is now a fixed cost for Omineca -- can you go into that a bit?

Tom MacNeill: One of the reasons we did that is we do not have a 43-101 compliant resource, nor are we likely to get one any time soon. Placer gold, as you know, is typically mined in private entities. That's why when we spent all of the money doing the initial bulk sample and investigation back in 2012. We did that in a private company CVG Gold, which still exists. It's a wholly-owned subsidiary of Omineca Mining.

Tom MacNeill: There are several reasons you do that. One, it's hard to calculate a resource on placer because of the intense nugget effect. The gold is trapped in certain riffles in the bedrock as you move along the stream. You can drill right next to an area that's rich in gold, but if you're six inches away then you're gonna get nothing. Or if you're six inches the other way then you may get a fissure that's filled with gold and a bonanza grade. It's difficult. You'd have to do a tremendous amount of work to get a resource. So we decided to do bulk sampling to get an idea of what we think is there and move forward. Then, the reason you end up with it in a public company is that we became aware in 2012 that there's probably some lode sources very, very close to this paleoplacer. That's the reason for having it in a public company -- people understand that. The cash flow that we're talking about, we've got the fixed-price contract because people can understand that even without a 43-101 resource calculation. We're not putting any upfront cost into the development of the bulk sampling and mining of this operation because we've already done.

Tom MacNeill: The relationship with our partners is that they bring their capital equipment, expertise, and all of their underground mining ability to bear. They've already started working last fall, by the way. They did quite a bit of work in 2019 on rehabilitation. They bring all of their expertise and get it to the point that they start mining it in the bulk sample phase. As soon as they break through into the pay channel and start liberating gold, they will own half the project. That means they will keep half the gold as they mine it. When they give us our half, they're going to give us a bill at a rate of $850 Canadian per ounce. Right now, we've got $2,350 Canadian an ounce. You can do the math on that.

Tom MacNeill: On that first ounce they give us, we would make a profit of $1,500. We're not going to talk about how many ounces we expect. We point people to what we recovered from the 2012 bulk sample, which was 173.5 one hundred and seventy-three and a half ounces from a 23.5 twenty-three and a half meter long drift with a standard 8x8 eight foot by eight foot crosscut that was 80 feet long. We got 173 ounces from that bulk sample. The immediate area of interest is 300 meters, where we will have 125 crosscuts that will be roughly the same as the bulk sampling. Some may be wider or narrower.

Tom MacNeill: We're as excited as anybody -- let's get mining! We'll see what we get and there's a visual that I have to point out. One of the things that we find exciting about paleoplacer that helps people make an estimation of what they think we might get is based on geotechnical work. Specifically, it is this salmon-colored area where we have a seismic reflection that we've done on the paleochannel. The gold area is the actual paleoplacer-bedrock interface where the old riverbed was located. This is where historical work suggests that it would be located and the yellow is where we found that it is located by seismic with some geotechnical drilling. Right here is where we did our 80-foot long crosscuts -- we came down the old workings and went down the stream that way. Now, we're going to repeat that 125 times down the first 300 meters here.

Tom MacNeill: The neat thing is that there is one, two, three, four five significant depressions in the bedrock contours of the old river channel -- that's where the gold usually gets trapped. We have a pretty high expectation that there will be enriched zones in lower areas of the old creek bed. That's an exciting prospect. We came in on a shoulder and were up pretty high, but we got a significant amount of gold out of that.

Tom MacNeill: Based on the non-compliant resource that was calculated in 1986 -- Bright Engineering is one of the best engineering groups in the world for calculating resources of any kind and they did a placer resource calculation in 1986 from over 1,500 meters at the Wingdam. They came up with 66,000 ounces of net potential. Based on that, we had an expectation going into this first crosscut and we nearly doubled our internal expectations. We were surprised. We got really excited about it.

Tom MacNeill: We've had a seven-year hiatus in the middle where we've done a lot of work in the background. Now the gold price is telling us to get underground and start liberating gold. Let's find out what's in the bottom of those five potholes in the first 300 meters. Then, let's go get the rest of the 2,400 meters in the immediate area of interest.

David Morgan: Very good, Tom. I'll keep my finance hat on for a while. First of all, this is a recommendation in the model portfolio in the speculative section of the Morgan report. I own the stock, for full disclosure. I already know the answer, but I need you to say -- please can I ask about the share structure and the price performance?

Tom MacNeill: We just recently raised a little over $1.5 million dollars. We priced that at 12 cents with a full warrant at 20 cents. The stock has responded very well to the activities that we started on site already. The share structure is really important. When we went into the financing, we had 84 million shares outstanding. When you add up insiders and the original founders of the company, CVG Mining -- the predecessor of Omineca, and all of the people involved with the original bulk sample at the private company stage, there are about 20 names that controlled approximately 75 percent of the stock. They're all vested in seeing the project through to its ultimate fruition. You have a situation where you have a very tightly held stock. We added 14 million shares on the financing, I believe it was. I think we're at 97 million shares undiluted. I think it's about 110 or 115 fully diluted. I guess it might be approaching 120, but we've got a unique situation where it genuinely is an incredibly tightly-held company because all of the people involved were first in it for the placer gold -- the prospect of cash flow from placer gold mining to be used for exploration of the hard rock potential gold sources around it. Nothing has changed.

Tom MacNeill: We've always been very upfront with our shareholder base that if we are successful with our partners in liberating gold from the paleoplacer project, we intend to use 50% for exploration of the hardrock sources in the immediate vicinity and the other 50% in special dividends to shareholders -- special dividends as they happen.

Tom MacNeill: We're not making any suggestions as to what we expect for cash flow. We left all of the bread crumbs for people to look at, showing what we've experienced in 2012 and what the historical record says about the paleoplacer. There is a record of 160 years of placer mining in the area and we've got some of the best technical guys in placer and hard rock mining in the region involved with this project -- it will be what it will be as we develop that. We view it as an excellent potential cash flow opportunity. It's one of those situations where you pay your money and take your chances, I guess.

Tom MacNeill: We just don't have any interest in spending $10-20M ten to twenty million dollars drilling off a compliant resource calculation on a deposit that we've already liberated a significant amount of gold from in 2012. We have a partner that's willing to take the risks with us.

David Morgan: You're not the only one. Not to dilute the conversation much, but Impact Silver's pretty much run a successful mining operation without a 43-101 and there are others that I'm familiar with. It's not an absolute requirement. Of course, what's so intriguing about this is several things. One, the size potential on the hardrock side. But another is the immediate cash flow from here. You're not going to squander it by putting a lot of money into the drill program and maybe you end up nowhere -- I've seen the ups and downs of the industry many times. Situations where companies spend $20M twenty million dollars on drilling, the cycle hits a low, and then someone picks up the whole project for a million and a half bucks! In contrast, this is a unique situation where you've got positive cash flow right from the get-go with a huge potential outside of it.

David Morgan: You're gonna take some of that money and you're gonna go explore. The possibilities for that could be extraordinary. These are the kinds of speculations I like. Something where you've got a guarantee that's going to be good and then, on top of that, you have outsized potential. I don't see too many of these situations. I'm famous for saying my favorite is a producer that's just starting that has lot of upside to increase their production rate and exploration potential. You fit the bill perfectly.

David Morgan: It's been a long time since I've been able to discover a situation like yours, Tom. I will go ahead and wrap it up. Is there anything that we haven't talked about?

Tom MacNeill: Not really. One observation, touching back on the paleoplacer work -- when we did our bulk sample, we found a certain character of the gold grains when we did the morphological analysis. Incidentally, several miles downstream of us there is an active placer operation that has gold that looks virtually identical to ours. You can say that we've got a high level of confidence that this continues to run probably both up and downstream. We have over 15 kilometers of potential paleoplacer pay channel.

Tom MacNeill: Now, one of the things that people asked is why should people care about Omineca. I have a quote from Steve Kocsis that came from our 2012 bulk sample report, which is a 43-101 compliant report. I encourage you to read. It says, "The deep lead channel contains some of the highest placer gold concentrations historically reported in all of the Cariboo mining district and perhaps throughout British Columbia that remains unmined." That's what got us excited.

Tom MacNeill: We love the paleoplacer because it can be a very immediate, near-term source of cash flow -- about a month to de-water once the pumps starts pumping, then a month's worth of underground workings and advancing the development drift with the access beside it, and then a month of getting things underway. This project can be several months away from cash flow. We actually produce cash flow from the bulk sample immediately once they break through into phase one. The thing that gets me excited about that is we want to go look for the hard rock, lode gold source.

Tom MacNeill: I've been in the gold mining business, especially, literally my whole life -- starting with exploration with my family back in the late '60s and early '70s. The hard rock potential is the most exciting thing I've seen in my career and I've been doing this for more than 35 years. We're genuinely excited about this. It's been great that we have such an expert group in the neighborhood in the form of Osisko doing great work just down the block on the same geology -- that allows us to piggyback on their work and save a lot of money by not doing things that we shouldn't be doing.

David Morgan: Tom, thank you very much for your time. I look forward to our next update.

Tom MacNeill: Thanks a lot, David. I appreciate it.